On the morning of September 29, 2024, the 73rd session of the THU History and Philosophy of Science Lecture Series was held in Room B206 of the Humanities Building. Professor Efthymios Nikolaidis from the National Hellenic Research Foundation (Greece) delivered a lecture titled "Byzantine Astronomy Under the Mongol Empire: Parallels and Contrasts with Contemporary Chinese Astronomy." Chaired by Associate Professor Shen Yubin, the event was attended by faculty and students from Tsinghua University, Peking University, the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and other institutions.

Lecture Content

- Defining Byzantine Astronomy

Professor Nikolaidis began by defining the spatiotemporal scope of "Byzantium" and its astronomical tradition. Core texts included Ptolemy’s Almagest and Theon of Alexandria’s Handy Tables, alongside Aristotelian cosmology shaped by Orthodox Christianity. In the 8th century, Ptolemaic astronomy was introduced to China by Nestorian exiles, including translations of astrological works like the Tetrabiblos.

- The First Byzantine Humanism (9th–11th Centuries)

A revival centered in Constantinople under figures like mathematician Leon (c. 790–869) involved editing Greek scientific manuscripts (the earliest surviving copies date to this period) and engaging with Arabic science. Michael Psellos (1018–1078) emerged as a leading scholar. Palaeographically, this era saw Greek script shift from uncial to minuscule for faster copying.

- Impact of the Fourth Crusade (1204)

The Latin sack of Constantinople ended this tradition: educational institutions (pandidaktirion) closed, manuscripts were looted, and scholars fled to Nicaea. Nikolaidis clarified that despite contemporaneous Mongol expansion, Byzantium remained unconquered by the Mongols.

- Pre-Maragha Arabic Influences

- Early Arabic impact appeared in the works of Stephanos the Astrologer (c. 775), who served Abbasid caliphs.

- Scholia in a 1032 Almagest manuscript (MS Vaticanus Graecus 1594) compared Ptolemaic star data with "modern" (neōteroi) observations (e.g., Ibn al-Aʿlam’s tables, 829 Damascus equinox measurements).

- The anonymous Methods of Calculation of Various Hypotheses (c. 1072) recorded a solar eclipse—rare in observation-averse Byzantine astronomy.

- The sole surviving Byzantine astrolabe (Brescia Civic Museums) bore Arabic-Persian inscriptions but was likely crafted for Byzantine users.

By the 12th century, Arabic astronomy was widely known, with Hellenized terminology.

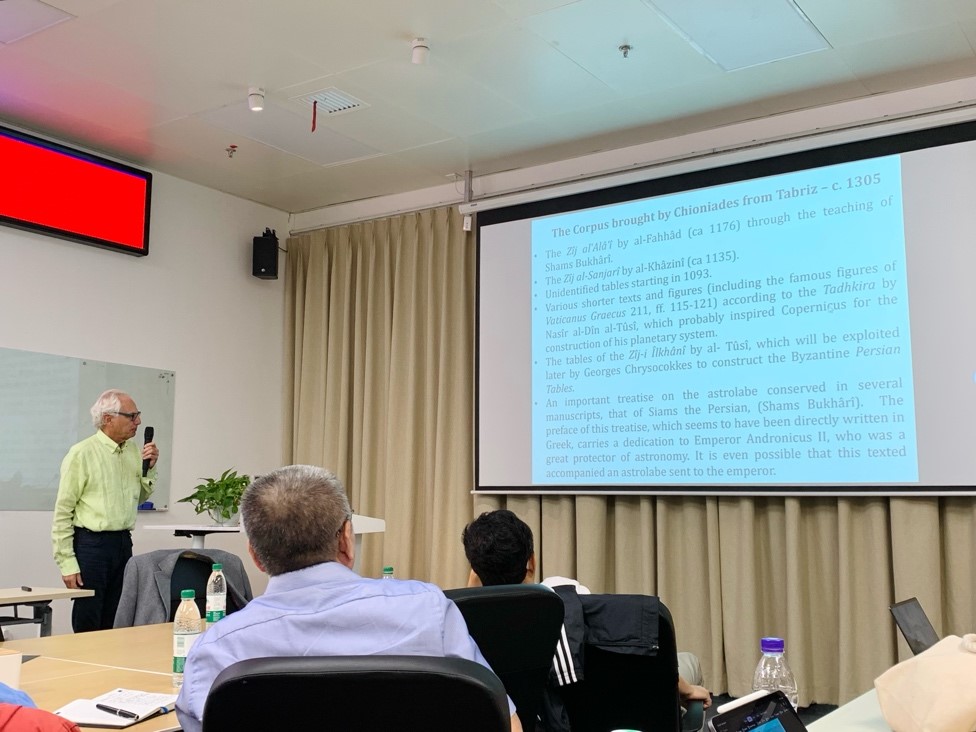

- Byzantine-Islamic Exchange at Maragha

Astronomer Georges Chioniades traveled from Constantinople to Tabriz via the Trebizond-Tabriz caravan after 1204. In Tabriz, he studied under Shams al-Dīn al-Bukhārī of the Maragha School, later translating Islamic texts into Greek (original Persian versions are lost).

- Dissemination and Synthesis

- Priest Manuel of Trebizond and his student George Chrysokokkes authored the Persian Syntax of Astronomy (c. 1347, unpublished), translating Nasir al-Din al-Tusi’s Zīj-i Īlkhānī and labeling the knowledge "Persian astronomy."

- Theodore Meliteniotes (c. 1320–1393), head of the Patriarchal School, wrote the Astronomical Tribiblos, comparing Ptolemaic and Persian methods. Byzantines abandoned rejecting Ptolemy as a "pagan," embracing synthesis.

- The Tusi Couple and Later Developments

Maragha knowledge included the Tusi-couple, later used by Copernicus (who cited Proclus but employed Tusi’s mechanism for Mercury). Copernicus accessed Greek manuscripts containing this model in Roman libraries.

In the 14th century, Byzantine eclipse calculations using Persian/Ptolemaic tables gained political significance amid bureaucratic debates. Concurrently, exchanges with Western Europe and Karaite Jewish networks facilitated Mediterranean knowledge transfer.

- Comparative Analysis: Byzantine vs. Chinese Astronomy

- Pre-Mongol Traditions:

- China: Indigenous astronomy with advanced instruments/observatories (continued under the Yuan).

- Byzantium: Ptolemaic-based, mathematically focused; no evidence of observatories.

- Observational Practices:

- Chinese were sky observers; Byzantines relied on mathematical calculations from imported tables.

- Postscript: 17th-Century Greek Interest in China

Orthodox ties to Tsarist Russia enabled Greek scholars like astronomer Chrysanthos Notaras to access Chinese knowledge via Russian diplomats. Nicolas Spathary’s 1674 Qing mission (meeting Ferdinand Verbiest) inspired Notaras’s writings based on Spathary’s reports and Martino Martini’s De Bello Tartarico, reigniting Byzantine interest in China.

Q&A Session

- Professor Wu Guosheng: Political implications of 14th-century eclipse debates.

- Dr. Alberto Bardi: Whether Spathary/Notaras carried astronomical tables.

- Dr. Guo Jinsong (Peking University): Byzantine use of the Zīj-i Īlkhānī.

- Dr. Wang Zheran: Defining the "Maragha School" and al-Tusi’s identity.

- Associate Professor Shen Yubin: Evidence linking Copernicus to the Tusi-couple.

Professor Nikolaidis addressed each query in detail.

Professor Wu Guosheng presented commemorative gifts from Tsinghua’s Department and Museum of the History of Science to conclude the event.

Documented by: Huang Zongbe

Reviewed by: Shen Yubin, Jiang Che